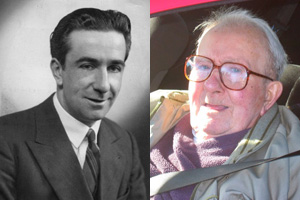

Ronald Peers Butler

December 27, 1924 - January 13, 2006

Eulogy delivered at his funeral service at the Garden of England Crematorium, Bobbing, on the morning of February 8, 2006

When I was a little boy I remember suddenly realising that my dad knew everything and that he was never wrong. That wasn’t because he was domineering. In fact I often didn’t accept some of the things he told me, only to find out later that I was the one who was wrong. Once after an episode of “Thunderbirds”, he gently pointed out to me that you would never be able to hear explosions in space because there were no sound waves in a vacuum. I’m glad he told me that, even though it spoiled every science fiction film I’ve seen since.

His wise words have stayed with me. When the family went up in an aeroplane together for the first time, me, my mum and my sister Penny were a bit nervous. My Dad wasn’t, because, he said that it wasn’t worth worrying about things over which you had no control. I still hear him saying those words if ever I’m flying and it makes me feel better. He told me that one of the best things in life was to find a job doing something you enjoyed, and those words changed my life.

He seemed to know all about the arts, music, literature, and with the Navy had travelled the world, but was very modest about all of that. Only by chance did I discover that he even had a lovely singing voice. The other year we found a reel-to-reel tape recording made in the 1960s where he is performing note-perfect versions of “The Green Green Grass of Home” and “Mona Lisa.” How he found time to learn all these things I’ll never know.

He taught me how to remember my times tables and right to the end was able to spell any word you put to him, without fail. He did everything needed around the house. We had countless family outings to every place of interest within driving distance. Museums, buildings, gardens, zoos. These things might not be fashionable with today’s youngsters but were magical memories for me growing up.

He let me stay up and watch the Eurovision Song Contest when I was eight and a few years later took me to Crystal Palace for the first time for an athletics meeting. More than ever now I treasure the many family holidays we had every year of my childhood with my dad at the wheel driving us all safely in a Ford Cortina.

He always had time to do these things and yet seemed to work all hours. I once got into trouble when I told people at school my dad was a window cleaner. Actually that was only his second job, he worked at Doultons potteries at the time. As well as that he took in some work at home. I couldn’t have been set a better example of the value of hard work, and I always remember my dad handing over his pay-packets – intact – to mum for household expenses.

When I started going out into the world I knew my dad would always be at the end of a telephone in case I needed a lift and I’m ashamed to say that I once called him out from Sheppey just to drive me from Rochester to Chatham. He should have complained to me about that but he never did. I think he was reliable to everyone. Whenever the telephone rang with an emergency at his work – and it often did at all hours – dad would be in the car and on site within minutes. In much sadder circumstances I remember how he gave unfailing support to my auntie Pat in her final weeks. One of the last things I heard her say was what a wonderful man he was.

After his first heart attack in 1992 my dad gave up work. He was as tough as old boots, once he agreed to having some teeth removed without anaesthetic because he was fed up with waiting for the injections to take effect. And he would enjoy telling the story of how he lost the tip of his little finger in a gate. Yet still was up and about in the mornings at least an hour before everyone else in the house, who he then served in bed with tea, toast and a newspaper that he hadn’t read himself. He never wanted much sleep and claimed that he never had a dream. If ever he heard as much as the chink of a teaspoon in the kitchen after dinner he’d shout “leave that”. He would do the washing up and clean the kitchen while the rest of us could go off and do what we liked.

It was hard to find presents for him, which made Christmas difficult because his birthday was just two days after Christmas Day. He never seemed to want anything for himself, he just wasn’t bothered about material things. I even remember him giving me his war medals to play with in the garden. I can tell you though, that he loved stilton, the violin, Charlotte Church, Rita from Coronation Street and salt, though he always put way too much of it on his food. He hated mushrooms, the harp – particularly when played by a woman – Madonna, television adverts for the endless sales at DFS, and despaired at the difficulties of penetrating ”modern bloody packaging.”

I must remember my dad with a smile because time and again he would tell me how important in life it was to have a sense of humour. I have happy memories of us watching TV or listening to the radio together and sharing a laugh. Or agreeing that certain less funny programmes were – as he always put it – “a heap of tripe”.

And he was sparkling in company to the end of his life. He had a knack for remembering people, remembering what he liked about them and reminding them of that when hey met again. They would warm to his kind nature. When visiting him in hospital, we found that everyone else in the ward would know and like my dad. We would ask for Mr Butler, but already he was known as Ron. He might have been ill but I think he enjoyed the attention. He never moaned about his condition apart from telling me in moments of discomfort “never get old.” He was more concerned with me and my mum than himself and I think the last words I heard him say to me were to drive carefully as winter set in.

He’s been my dad for 45 years and married to my mum for 53 years. People ask what was their secret and I always say they were experts at looking after people. First it was my dad looking after my mum, then the other was around and I must pay tribute to you mum for fighting so hard to make him comfortable in his final years.

Dad, I’m sorry that I could not do a fraction of the things for you that you did for me. I would have loved to have taken you to Tibet, you always wanted to go there, or have you stay in my house when it is ready, or cook a you a meal or drive you across the new Sheppey Crossing and a thousand other things. But you’ll be with me again when I think of you and I always will.